Staff Spotlight: Westminster Security Head Provided Protection for U.S. Presidents

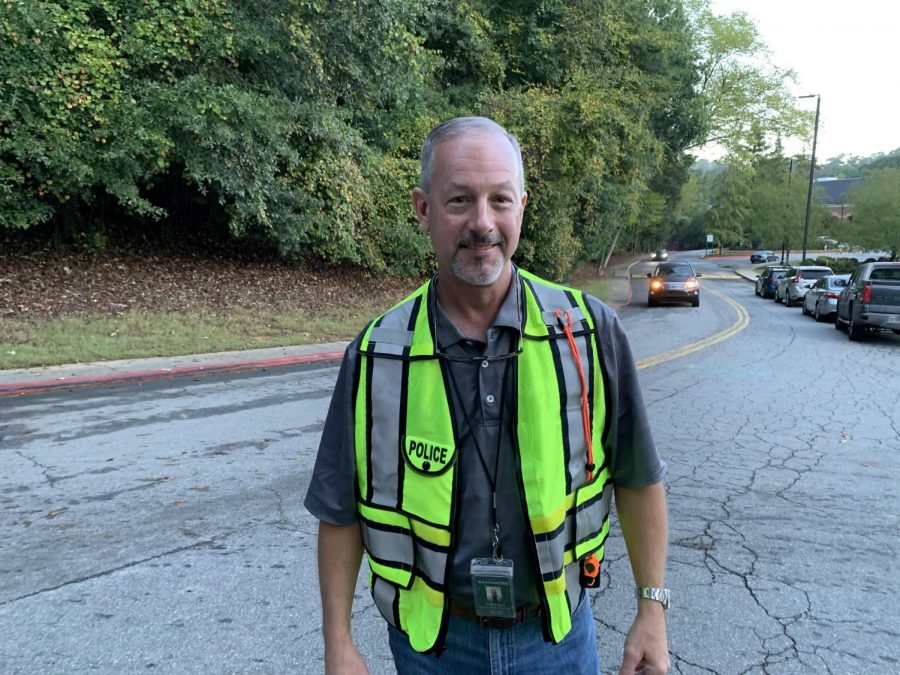

As your car swerves through the twists and turns of Westminster’s campus roads, you recognize Mr. Spivey, who’s directing the morning stream of cars. Most of us don’t think much of him––he’s only a traffic guard, right? Wrong. It turns out, the man who tells you to “turn right” every morning actually has a rich history of protecting U.S. Presidents with the Secret Service.

Spivey was in college when his interest in law enforcement drew him to apply for the Secret Service. “I thought, if I’m going to pursue law enforcement, I’m gonna shoot for the top,” says Spivey. “I wanted to try something really challenging and rewarding. That’s when I chose the Secret Service.” However, his application process took several years. “It’s a difficult process to go through in terms of background investigation and all of the things that they have to do to check you out, to make sure that you’re worthy. You get a security clearance whenever you come on the job, which means that you’ve been cleared to keep certain government secrets.” A background check is required to ensure the applicant has no past conflicts which cause future issues. However, Spivey’s wait proved to be rewarding in the end. “It was worth the wait, it was worth the effort,” says Spivey.

When most think of the Secret Service, they usually think of the presidential protection mission. However, the Secret Service originally served a different purpose, to suppress and investigate counterfeit money. The printing and distribution of counterfeit money by the Confederate Army posed an enormous threat to the U.S. government and economy during the Civil War. This law-enforcement role continues to this day. “The investigation side was really what you call white-collar crimes––fraud, counterfeit currency, it became bank fraud, and later years and current times, it became cyber fraud,” explains Spivey. “We worked on a lot of technical cases that involved tracing money, money laundering, and determining where money is being hidden or created.” The majority of counterfeit money is printed within foreign countries and is then covertly shipped to the United States for use.

It wasn’t until when President McKinley was assassinated in 1901, the Secret Service unit began its mission of providing protection for the U.S. Presidents.

During Spivey’s 22-year tenure, he secured six U.S. Presidents. Four were Presidents in-office, while two were ex-presidents. “The first President that I protected when I came on duty was President Bill Clinton, then there was President George Bush for two terms, and then President Obama for two terms, and then part of President Trump’s presidency before I retired,” says Spivey. “The former Presidents that I protected were Jimmy Carter and H.W. Bush, who was George Bush’s father.”

A day in the life of an agent is difficult to describe, as every day is unique. It depends on where the agent is located, or the assignment itself. “For example, if I was assigned as a field agent in Atlanta, I could be working on an investigative case, a counterfeit case, or a money laundering case one day, and travel orders would come out, and say: the President’s gonna need you in Iowa in three days,” says Spivey. “I have to drop what I’m doing, go home, pack a bag, make sure I have all the arrangements and get to Iowa in advance of the President getting there.” Being a Secret Service agent calls for short-notice orders, which can prove stressful at times. “I could be on the road traveling, and orders come out again, and say: we need you to go from Iowa to Nebraska whenever I thought I was coming home, but it’s sort of a curveball––you don’t know what your next plan is. You’re working for the mission.”

Throughout his career, Spivey grew to appreciate the level of trust placed in him to complete assignments. The government placed him in situations where he was capable of making decisions greatly affecting a vital outcome. “It’s just a huge amount of responsibility given to a Secret Service agent when they come on the job, and as you grow in your career, things tend to increase,” says Spivey. However, the job contains a few downsides, especially time spent away from loved ones. “There’s a lot of traveling involved, there’s a lot of time away from your family, you’re gonna miss holidays, birthdays, special events,” says Spivey. “Your family has to understand what your career is about and what it’s like. Fortunately, my family was very good with that, and they adjusted and accepted it very well. It was harder on me to miss those events than it was on them because they became accustomed to knowing that I wouldn’t be there.”

Secret Service agents become eligible for retirement once they reach a particular age and have a certain number of years of service. Spivey reached his retirement eligibility at age 52. “When I became eligible to retire, I decided I wanted to retire at a young enough age that I could be marketable to find a second job. Also, with the federal law enforcement and Secret Service, you have to retire by age 57,” says Spivey. “I was at age 52 when I retired––I could have gone five more years, but it really wasn’t that beneficial for me to stay there. It was more beneficial for me to come out at 52, find that second career, and start that.”

Spivey learned a number of valuable lessons while working as a Secret Service agent, one being to remain tolerant of others. “Being a Secret Service agent, you’re in a political environment. At any given time, you could be exposed to a political viewpoint or to a political party that you don’t necessarily agree with,” Spivey says. “Your call to duty and your response is paramount over personal feelings. It teaches you to be accepting, it teaches you that regardless of your political ideology or position, the mission comes first.” Today, Spivey applies this lesson when working his security position at Westminster. Regardless of personal beliefs and opinions, Spivey focuses on the task at hand: to provide unlimited protection to all members of the Westminster community.