In Depth: Recycling Issues at Westminster Spark Debate

Picture this; you’ve just come back from sports practice and you’ve just finished up your plastic recyclable water bottle. So, as you walk back to Clarkson, you throw it into the recycling bin. All done, right? Well, maybe not. As it turns out, that specific bottle probably will not be recycled at all. Westminster has to throw away quite a few batches of recyclables every day—and it might just be because of students.

Westminster has a history of promoting recycling and sustainable lifestyles to its students. However, during the past few years, students and faculty have openly questioned whether the waste in the recycling bins might actually be sent to the landfill. The question of whether or not Westminster recycles is actually not that simple. Hartley Glass, a civic engagement coordinator at Westminster, believes that the issue is rather multifaceted. “It’s not that the school completely doesn’t recycle,” she says. “For example, I know that we do recycle [material] like cardboard boxes that have been flattened in the facilities department. It’s just the recycling bins in the classrooms and in the lunchroom that they have decided not to recycle for whatever reason. But in the past, I believe that they did.”

According to Vice President of Finance and Operations Toni Boyd, Westminster’s failure to recycle mainly lies in the hands of the students and faculty. “Well, everything that we do with respect to recycling starts with students and faculty,” Boyd states. “So Westminster does recycle. Westminster has never stopped recycling. You make a conscious decision whether you’re going to throw something in the recycling site or the landfill site. That’s really where it all begins. With respect to personal participation . . . One of the challenges that we have is if you throw food in the single-stream recycle bin, then I can’t send that to get it sorted and recycled.” According to Boyd, recycling contaminated with trash will be rejected at the single-stream sorting plant.

Glass agrees. “[It’s] an issue of students not fully understanding the difference between what can be recycled and what can’t be recycled. And when non-recyclable materials get co-mingled with the recyclable materials, then they have to throw the whole batch out because you can’t separate those two things. So I think there’s, on one level, an issue of not quite trusting students and teachers enough to be able to really do it, to separate the things.”

Because the students and faculty have continued to throw trash into recycling bins, the sanitation crew and administrators have decided to simply stop sorting through the recycling bins and send all waste to the landfill. Moreover, there’s also a cost factor. The recycling bins can be sorted at the plant to remove trash, but the school doesn’t want to pay the extra money. “It’s expensive to recycle and especially if the recyclables and non-recyclables are commingled and mixed up,” says Glass. “It’s really expensive to have to sort that out through the city of Atlanta. And so I think it’s a cost thing, too.” Boyd also agrees that cost is an issue when dealing with sustainability. “There is a price point in which we say it’s not fair to your families paying tuition for me to focus on that,” Boyd states. “There’s a breakpoint somewhere, but we’re very attentive to what that is.”

Boyd and Glass both believe that the best solution to this issue is to educate and promote recycling in our community. “I think the first step would be education for the students and the teachers about what can and cannot be recycled,” says Glass. Boyd pushes for students to take leadership and help promote recycling. “I think the biggest thing you could do is, in Middle School, promote recycling,” Boyd states. “Whether that is through a contest, who can recycle the most . . . what grade, class, produces the least trash. Because that’s really where it starts. [The problem] is not managing the trash—it’s creating the trash to begin with . . . But what that also does is create habits and attitudes around producing less waste and seeking out recycling.”

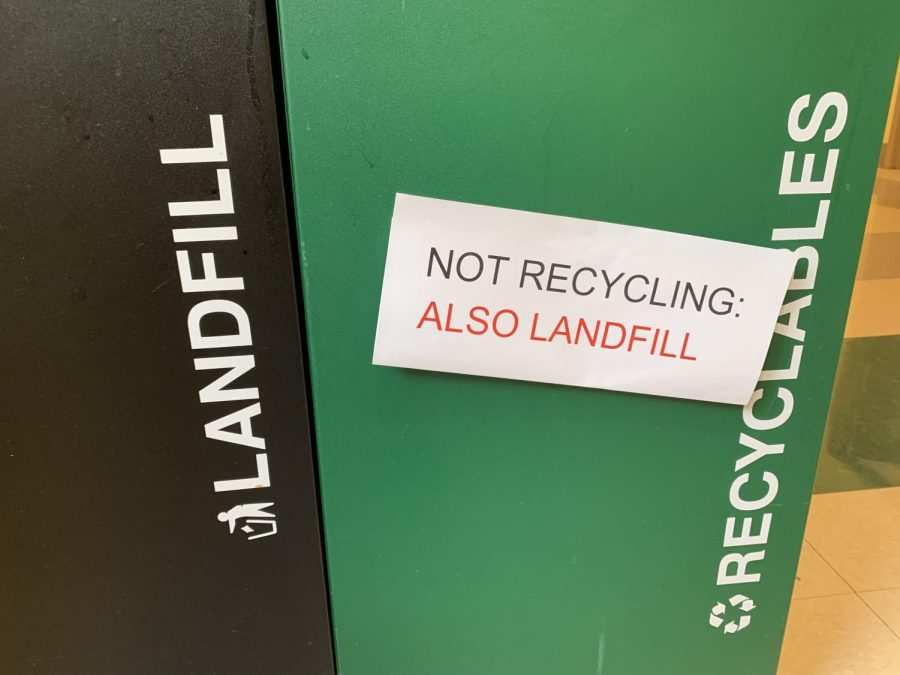

In the past, Westminster has made attempts to educate students about the importance of recycling and what types of waste should be disposed of in which bins. However, this campaign was mostly limited to signs above the recycling cans, which did not prove to be very effective. According to Head of Middle School Danette Morton, “There was just signage and information around campus about recycling, whether that was . . . a piece of paper on a recycling bin that said, ‘Recycle this, that, the other. Don’t recycle . . . something else.’” Morton admits that this campaign was not very effective. She states, “I will say that while there was a little bit more of a visual campaign for recycling . . . I don’t ever remember the actual usage of or participation in that campaign being very strong, meaning there was almost always trash in the recycling bins.”

Another independent school in the area, the Marist School, has faced many of the same problems as our school. However, they have managed to continue recycling the waste in the bins used by students and faculty. For starters, the sanitation team checks the recycling bins for any sort of non-recyclable materials. According to Director of Campus and Student Activities and Sustainability at Marist Amelia Luke, “Our housekeeping keeps an eye on it, and if they see anything trash wise egregious in a recycling bin, they’ll pull it out so we don’t have to toss the entire container full. We occasionally get reports from our recycling hauler about any major contamination. If they’re seeing anything as well that we can sort of back up.”

However, Luke still agrees that the most important factor in helping Marist’s ability to recycle more is educating students about what can and cannot be recycled. The school has organized many campaigns to teach students about recycling, many of which have proven very effective. For example, the school’s environmental sciences club plays a significant role in educating students about separating recyclable materials from landfill. “We’ve used our environmental science class quite a bit to help make changes,” Luke states. “We’ve had them standing in at the trash and recycling and compost bins at lunch, making sure that people know how to sort it. And they’ve created new and different signs every year or so to help educate the kids wherever there are trash cans and waste cans.”

Marist’s teachers also play a large role in educating students about recycling. “I rely on teachers a lot, too, to just sort of keep an eye on it and make sure that their kids are [managing waste] the right way in the classroom,” she says. “We found success in having our science teachers talk about it at the beginning of the year. And we have a couple of science teachers that give quizzes throughout the term to students about what they’re supposed to do with certain items . . . If it’s something they have to study for for a grade, they’re much more likely to do it and do it well.”

One of Marist’s most effective campaigns is a “trash audit,” where the students will sort through the waste produced during one day in the cafeteria. “We have run programs with our middle school students where we do a big trash audit from only really one day’s worth of trash from our cafeteria,” says Luke. “We sent all of the garbage bags and had the kids sort it into what could have been recycled and what could have been composted and what could have been saved and donated because it wasn’t even touched.” These audits provide quantitative data about how well waste is being handled and educate students about proper disposal of waste.

Westminster students find themselves frustrated and confused over Westminster’s shortcomings in recycling and reluctance to admit the issues. 6th grader Burke Stephenson expresses his annoyance over the matter. “I feel really lied to because I thought Westminster was good about [recycling],” he states. “But apparently they’re not. So we need to work on that.”

8th grade student Aly Adams, a member of the sustainability group in the 8th Grade Leadership elective, believes that Westminster doesn’t explain its issues and goals clearly to its campus body to maintain their reputation. “Being a major campus and everything, I think they just don’t want people to know that we don’t recycle,” Adams states. “I think they need to let us know that we don’t recycle some items, but like everything, I think Westminster doesn’t tell us because they want to keep their [reputation] because we’re a nice school.”

In a recent interview, Morton admits that even she is in the dark over this matter. “I’m realizing how little I know about the current state of recycling at Westminster,” she states. “So this is an area that I need to be better versed in and I need to get an update on information.”